From Crude to Compute: Building the GCC AI Stack

Executive Summary

-

The six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member states — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates — are all, to various degrees, pursuing the development and adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. This requires the creation of a full AI “stack” — a comprehensive, end-to-end digital ecosystem spanning the entire value chain, from specialized silicon chip production to software to data-processing facilities. A GCC AI stack envisions coordination on computational power (“compute”) infrastructure buildup and investment, energy interoperability, and grid and regulatory harmonization.

-

The GCC’s core goal is to establish the Gulf globally as a critical and trusted AI node. For the United States, the objective is to fully integrate the GCC players into the techno-economic networks of the US and its allies, creating commercial opportunities for American firms to offer compute as a service for emerging markets that either cannot build enough compute or cannot build it at all.

AI Stack The term stack draws inspiration from India's successful digital transformation through India Stack – a framework of digital identity, payment, and data-sharing platforms. Building on this foundation, the concept of an AI stack in India has evolved further through initiatives such as IndiaAI Mission and the Centres of Excellence for AI. The programs lie at the heart of India’s AI transformation while expanding access to high-performing compute with approximately 38,000 GPU-equivalent units already deployed, a national dataset platform (AI Kosh), supporting startups, and encouraging research. India’s approach is incremental and scale-aware, scaling infrastructure while ensuring public accessibility and affordabilityThe GCC needs to coordinate the expansion of the regional electric grid for data integration and establish an integrated, resource-sharing compute network. GCC member states should also rapidly develop indigenous talent through AI labs, educational programs, and talent pooling from neighboring states (e.g., Egypt, Jordan, Syria, and Iraq).

-

Creating a Gulf region-wide AI stack promises to yield enormous benefits for the GCC’s collective AI ambitions and capabilities. This project will of course also face numerous challenges, but these can be overcome with know-how and determination. Forging the GCC AI stack should be a priority for the United States as it shapes its AI and technology policy for the Gulf, especially as the region moves quickly toward becoming a hub for AI infrastructure. The advantages — for the Gulf as well as the US — that would accrue from success would more than justify the parallel effort required to do so.

-

The underlying impetus for the creation of the GCC stack is rooted in the region’s abundant, stable, and scalable energy supply (including oil, natural gas, growing renewables, and now nuclear power), which provides a structural advantage for a massive compute buildup over energy-constrained global powers like the European Union.

-

The GCC stack has the potential to create a third major global node of compute capacity — in addition to those of the US and China. But critically, the GCC stack will be commercially and technically aligned with American firms, thus serving as a force multiplier for US AI capacity that can outscale China’s diffusion of its own AI stack, through the Digital Silk Road, into the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

-

The GCC should adopt a sequential coordination strategy: build national compute capacity rapidly, then join it together across the region. This will leverage the speed and urgency of national initiatives (led by the UAE and Saudi Arabia) as a foundation for the subsequent development of an integrated Gulf compute network. Such an approach should avoid both the paralysis of waiting for a perfect regional consensus, on the one hand, and the costly waste of permanent fragmentation, such as that seen in Europe, on the other.

-

Thanks to Gulf states’ deals with the United States to secure chips, combined with their low energy costs, massive capital availability (especially through the region’s sovereign wealth funds), and a clear political commitment to AI, the GCC region could collectively account for 5-10% of new global AI-optimized graphics processing unit (GPU) deployments over the next decade.The US requires the GCC’s energy and capital to build out new compute capacity, while the GCC needs guaranteed access to America’s unparalleled AI chips and technical talent; this interdependence necessitates a formal US-GCC AI Compact or Framework Agreement.

-

This GCC-centric infrastructure would create significant spillover effects across countries and regions bordering the Arabian Gulf, enabling these neighboring states’ participation through AI infrastructure, shared compute access, and regional talent pooling — bringing them into the US-GCC AI ecosystem and ultimately forging a broader techno-industrial bloc across West Asia.

-

The US needs to clarify its investment policy, particularly regarding regulations or possible limitations coming from the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), and designate GCC countries as trusted AI allies with expedited processes to overcome current policy uncertainty and export control delays.

Repositioning the AI Question Around Compute

To diversify and future-proof their economies, the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states — Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Bahrain, and Oman — have all undertaken efforts to adopt as well as indigenously develop artificial intelligence (AI) technology. This necessitates building a complete ecosystem of AI infrastructure, encompassing everything required to develop and operate the technology at scale: advanced semiconductor chips, massive data centers, reliable energy supplies, substantial capital, technical talent, and physical connectivity through undersea cables and network infrastructure. This integrated system differs fundamentally from previous national assets. Its scale, cost, and scarcity map directly onto national power in new ways that demand closer examination.

Training frontier AI models requires these elements to work in concert. Each represents a genuine constraint on which states can compete at the highest levels. Specifically, what distinguishes computational power, also known as “compute,”[1] from other infrastructure is its tiered nature. Roads and electricity are necessary and ubiquitous. Compute infrastructure is scarce and multiplies power for whoever controls it. Access requires the newest chips, the capital to acquire them at scale, the energy systems to power them, the technical expertise to integrate thousands of units into large data centers, and the connectivity to move massive datasets efficiently. Missing any piece eliminates a country from serious competition.

The GCC states occupy a unique position in this context, thanks to the region’s comparative advantage in control of multiple critical inputs, including energy and capital, as well as in its geography.

The GCC’s energy infrastructure produces competitively priced power and can scale to meet compute demands. The six Gulf states hold 21.4% of global natural gas reserves, 32.6% of world crude oil reserves, and 28.2% of total global crude exports.[2] Furthermore, total GCC power generation in 2023 was approximately 755.9 terawatt-hours (TWh), placing the Gulf among the higher-output regions globally in per-capita or regional comparisons.[3]

The natural resources of the Gulf provide it not only with energy but also with deployable capital. The region’s sovereign wealth funds (SWFs), which are measured in the hundreds of billions of dollars, provide the capital that makes large-scale investments manageable in ways that are not replicable for most countries. Three of the six GCC states are in the top 20 wealthiest states in the world by GDP per capita, and the region is home to four of the world’s 10 largest SWFs.

Geographic positioning between continents already makes the Gulf a natural global node for undersea cable networks connecting Asia, Europe, and Africa. As a result, the GCC is well positioned to serve rapidly growing emerging information-technology markets across the Middle East, Africa, and South and Southeast Asia.

What remains for the Gulf is acquiring access to advanced chips, building the data center infrastructure, and developing the technical talent pool needed to form a robust AI sector at home. These are achievable objectives with the right partnerships and strategic focus.

Development of a Gulf AI stack — the layered AI ecosystem from hardware to software — creates a third major international node of compute capacity, after the United States and China, in a region with deep commercial ties to American technology firms, using American chips and often American technical partnerships. Geopolitically, the Gulf AI stack expands AI capacity beyond China while generating substantial commercial opportunities for US semiconductor manufacturers, cloud providers, and AI labs. The Gulf becomes not only a meaningful buyer of American technology at scale but also a development partner for applications serving markets across the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

![Photo above: People walk past a Huawei stand during the third day of the Web Summit in Doha, Qatar, on February 25, 2025. Photo by Noushad Thekkayil/NurPhoto via Getty Images.[/caption]](https://www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/Huawei%20in%20Qatar%20via%20GettyImages-2201353351.jpg)

The US Stack Versus the China Stack

At present, and for the foreseeable future, the United States is locked in a battle with China over dominance and innovation in AI. Which country triumphs will have decisive implications for both, and for the rest of the world. A key reason that a GCC AI stack should be an American priority is the huge advantage it promises to offer the US in this competition with China and strengthen its overall technological position in the 21st century.

The American AI stack is the world’s most advanced and globally diffused. The top AI research labs, such as OpenAI, Anthropic, DeepMind US, and many more, are all based in the United States. Furthermore, the US also leads the world in cloud compute capacity, purchasing roughly the same amount as the rest of the world combined.[4] Companies like Amazon Web Services (AWS) and Google Cloud, both examples of top cloud creators, are similarly based in the US. However, the global race for AI dominance is intensifying, and the United States wants American technology to be the global standard so as not to cede this position to its greatest adversary in the AI race — China. The current administration hopes that American technology, like the US dollar, is adopted around the world. In the AI Action Plan, released in July 2025 as part of the government’s strategy to maintain global AI leadership, President Donald Trump declared that “it is a national security imperative for the United States to achieve and maintain unquestioned and unchallenged global technological dominance.”[5] The AI Action Plan provides a comprehensive roadmap for advancing US leadership in AI built around three key pillars: innovation, infrastructure, and international diplomacy and security.[6]

At the core of this competition is the AI stack, which not only determines how AI is developed, but gives states influence over global supply chains and the ability to shape emerging markets. As the United States and China race to export their respective AI infrastructures, regions like the Middle East, Africa, and Southeast Asia are becoming key battlegrounds for market share and long-term geopolitical dominance.

Nevertheless, the United States remains the global leader in high-performance AI chips and advanced computing infrastructure. US technology giant NVIDIA still designs the most advanced AI chips, which are a key component of training AI models. Combined with its software framework CUDA, NVIDIA’s graphics processing units (GPUs) continue to be the preferred option for training frontier AI models. Today, most of America’s leading models, including OpenAI’s ChatGPT Series, were trained using NVIDIA’s A100 chip.[7]

The US also leads in AI infrastructure, which most critically includes data centers. AI data centers are mega-scale facilities where AI training takes place. American hyperscalers like AWS and Microsoft Azure are the dominant players in the global construction of AI data centers.

Future leadership is not guaranteed. The American stack is not without vulnerabilities. There are supply chain bottlenecks and massive energy requirements, with which the United States is already struggling. Internationally, US government policy has shifted away from containment to strategic diffusion. The Biden administration’s AI Diffusion Rule imposed strict export controls on US-made AI chips aimed at constraining adversaries’ AI capabilities. That policy was changed by the Trump administration in May 2025. Soon after President Trump visited Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, establishing key partnerships centered around AI. One of the many projects agreed upon is Stargate UAE, an ambitious plan to build a 5-gigawatt (GW) data center campus in Abu Dhabi with American technology.

Current and foreseeable American AI policy thus sets itself the goal of winning the global AI race by rapidly scaling its technology and ensuring it becomes the base layer upon which other nations build their own systems.

Meanwhile, China is rapidly closing the gap on America’s AI dominance. China has spent the last decade building its own AI stack, prioritizing self-sufficiency. While China still trails the US in AI chip design, Chinese companies like Huawei are rapidly gaining ground. Huawei’s latest chip product, the Ascend 910C, is only one generation behind the US’s most advanced offerings, narrowing the gap to two to three years.[8] China has also invested heavily in the industry, claiming the world’s largest data center as of July 2025.[9] But despite these advances, China still does not have the chip-scale capacity for multi-gigawatt deployments of frontier-class compute — yet. Its bottleneck is not ambition or industrial policy; it is the ability to manufacture and deploy advanced accelerators overseas at scale. That constraint gives the United States a critical window to lock the Gulf into its AI ecosystem. Beijing may close the gap in a few years, but for now, the US remains the only player capable of supporting gigawatt-level AI infrastructure in the region.

Moreover, China’s greatest advantage across the AI stack is its energy leadership, where the United States falls well short. China added the equivalent of an entire US grid of capacity in the last decade.[10] It also dominates the renewable energy manufacturing sector, controlling 80% of the world’s solar panel production, as well as in the production of batteries, wind turbines, and electricity vehicles.[11] China approved the construction of 10 new nuclear reactors this year and is using its nuclear capabilities to extend its strategic influence, aiming to export 30 nuclear reactors to Belt and Road Initiative partners by 2030.[12] And while China’s manufacturing strength poses a long-term challenge — if Beijing can apply that scale to cutting-edge chips, it can flood the world with “good enough” accelerators at low cost — it still cannot produce or deploy advanced chips at gigawatt scale.

China is rolling out a staggering amount of new electricity capacity, adding more than 210 GW of solar capacity in the first half of 2025 alone.[13] For comparison, the entire US solar fleet will reach only about 182 GW by the end of 2026 — meaning China added more solar in six months than the United States will have installed in its entire history.[14] This massive scale of deployment is driven by China's dual carbon goals and its rapid electrification.[15] By comparison, the US has a total installed electricity generating capacity of approximately 1,250 GW, with projected additions of 400 to 600 GW of new capacity between now and 2040.[16] This shows just how rapidly China is building its electricity grid compared to the US. In a little over six months, China is deploying a large share of what the US plans to add over the next 15 years.

Furthermore, at the center of China’s AI strategy is the diffusion of its AI stack. While Chinese AI chips are still behind NVIDIA’s GPUs, Huawei is targeting smaller markets in the Middle East and Southeast Asia where both demand for compute and need for low prices are priorities. According to Bernama, Malaysia’s national news agency, “Malaysia has become the first nation outside of China to deploy Huawei’s Ascend GPU-powered AI servers, along with the open-source DeepSeek large language model (LLM), at a national level as part of the country’s push for data sovereignty.”[17] Huawei also opened an AI data center in Riyadh in September 2023.[18]

The combination of China’s rapid development and diffusion of AI with the energy and industrial capacity shortfalls of the US mean that the US cannot, as it took for granted in the past, win the AI race alone. It must rely on strategic partners, and together, they can ensure the US AI stack dominates around the world. Nothing better exemplifies this vision than Vice President JD Vance’s speech at the 2025 AI Action Summit in Paris, where he declared that “America wants to partner with all of you,” adding that the Trump administration will ensure the US is “the partner of choice for others — foreign countries and certainly businesses — as they expand their own use of AI.”[19]

![Photo above: Guests look at a model of a data center under construction in the UAE as part of the Stargate initiative, a joint venture between G42, Microsoft, and OpenAI, during the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference (ADIPEC) in Abu Dhabi on November 3, 2025. Photo by Giuseppe Cacace/AFP via Getty Images.[/caption]](https://www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/inline-images/UAE%20data%20center%20via%20GettyImages-2244358004.jpg)

What Is the GCC AI Stack?

The Gulf AI stack represents a comprehensive infrastructure framework designed to build regional capacity across the entire AI value chain — from semiconductor access and compute infrastructure to model development, talent, and connectivity.

The Gulf states should take an expansive approach to developing a regional stack. A Gulf AI stack would encompass the region’s integrated compute infrastructure: advanced chips, massive data centers, energy systems, capital deployment, technical talent, and physical connectivity through cables and networks. The concept envisions a Gulf ecosystem capable of training frontier models, running large-scale inference for emerging markets, developing applications for regional and global users, and serving as a strategically positioned node in the global AI architecture — particularly for markets across the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

Establishing the GCC AI stack would do the following:

-

Elevate the Gulf states’ internal AI capabilities, enhance interoperability, and coordinate the buildup of AI infrastructure.

-

Position the GCC globally as a trusted and integrated partner within the techno-economic networks of the United States and its allies, thereby creating substantial commercial opportunities for American technology firms.

-

Generate strategic spillover effects in neighboring states — including Iraq, Jordan, Egypt, and potentially Pakistan — by providing compute capacity, large-scale inference services, technical partnerships, and connectivity infrastructure that accelerate their digital transformation while keeping them aligned with US-compatible technology standards rather than Chinese alternatives.

-

Forge a broader techno-industrial bloc spanning the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean, advancing regional economic integration through shared AI infrastructure, harmonized regulatory frameworks, talent mobility, and cross-border connectivity. This bloc would position the region as a third major node in the global AI architecture — commercially and technically integrated with American firms — while serving emerging markets across the Middle East, North Africa, and South Asia that together represent more than 1.5 billion people.

These four goals — internal capability enhancement, trusted partnership with the US and allies, strategic regional spillover effects, and broader techno-industrial bloc formation — are ambitious but achievable. Their feasibility rests on a fundamental advantage that distinguishes the GCC from other aspiring AI regions: energy abundance. While much attention in AI discourse focuses on chips, talent, and capital, the constraint increasingly binding advanced economies is reliable, scalable, and affordable energy supply. Here, the Gulf possesses a decisive structural advantage. This is not an either-or proposition for Washington. The United States must expand its own energy capacity while simultaneously working with the Gulf. Domestic buildout, on its own, cannot meet the scale or pace of AI-driven electricity demand; yet exclusively relying on foreign partners would introduce unacceptable strategic risk. The logic is therefore a “both-and” approach: reinforce America’s internal energy resilience while anchoring the Gulf as a reliable, long-term extension of the US AI ecosystem.

Constructing a regional techno-industrial bloc is not an easy feat. It requires immense capital, adept coordination, and political agility. However, the GCC states have already signaled their collective ambition to participate in the AI landscape, moving beyond passive financial investment in foreign AI companies toward building operational compute infrastructure within the region. The UAE, following agreements with US firms, including partnerships with Microsoft, OpenAI, and commitments from NVIDIA for advanced chip access, could potentially host a substantial portion of new global AI compute capacity over the next five years. Similarly, Saudi Arabia, through partnerships with AWS and NVIDIA, is positioned to expand its capacity significantly. The Gulf region collectively could account for a significant share of new global AI-optimized GPU deployments, though this ultimately depends on chip-export approvals that enable the infrastructure buildout.

Why a GCC AI Stack?

Some have suggested that the uneven and fractious political development of the Gulf makes it less able and less desirable as the host of a new AI stack than Europe. Yet by comparison, the European Union (EU) — despite its larger economy and population — faces significant constraints in compute buildout due to energy costs, regulatory constraints, and capital allocation challenges, with estimates suggesting Europe may account for less than 5% of new AI-optimized compute capacity during the same period.[20] This stark contrast in projected capacity — where the Gulf could potentially deploy significantly more new AI compute infrastructure than the entire EU — reflects fundamental advantages in energy costs, available capital, and political coordination that Europe struggles to match. This difference is precisely why the architecture of the GCC's eventual AI stack is so vital.

The EU currently imports approximately 80% of its semiconductors and relies heavily on non-European cloud infrastructure, prompting various initiatives aimed at building greater digital autonomy — including the European Chips Act and increased funding for AI research through Horizon Europe, the EU’s flagship research and innovation program.[21] However, Europe’s goal to establish a digital strategic autonomy stack faces obstacles, including scaling challenges, significant investment gaps compared to global competitors, talent shortages in key areas, and supply chain dependencies.[22] More fundamentally, Europe struggles with regulatory fragmentation across 27 member states, higher energy costs than the Gulf or the US, and limited risk capital compared to American venture funding or Gulf sovereign wealth.[23]

The European experience — attempting to build coordinated digital infrastructure across multiple sovereign states with competing national champions and objectives — offers instructive lessons for the GCC, both positive and cautionary. Europe’s struggles illustrate how fragmentation undermines scale: with individual member states pursuing separate AI initiatives, duplicative data center investments, and little coordination on compute integration, the continent remains structurally disadvantaged despite its vast economic size and technical talent.

The GCC should avoid repeating Europe’s mistake of fragmentation — a topic addressed in greater detail below — but it must also recognize that building national stacks represents a necessary and pragmatic first step. Individual GCC member states possess the capital, political will, and urgency to move quickly on compute infrastructure. These national initiatives serve as essential catalysts, kickstarting capacity that might stall if dependent on full regional consensus from the outset. However, this initial phase of national stack development must be explicitly designed as a foundation for subsequent regional integration, not an end state. In this vein, they should recognize that capacity alone is insufficient: the Gulf must also develop the technical talent, operational expertise, and application ecosystem to make this infrastructure productive rather than merely present.

The Gulf should leverage its existing coordination mechanisms through the GCC framework to establish from the beginning a clear pathway toward bringing these national capabilities together into an integrated regional Gulf AI stack built on shared connectivity, strategically coordinated data center placement, common technical standards, interoperable regulatory frameworks, and pooled talent development across borders. The hybrid strategy means accepting that the UAE and Saudi Arabia will lead initial buildout based on their advanced partnerships with US firms, while simultaneously ensuring that other states, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, and Qatar, can plug into this emerging infrastructure through coordinated planning rather than watching from the sidelines.

Unlike Europe, the GCC benefits from significantly fewer regulatory barriers, closely aligned economic interests, substantial existing energy integration, geographic proximity that makes physical connectivity far simpler, and concentrated decision-making through SWFs that can commit capital at scale without navigating complex parliamentary budget processes or state aid regulations. Most critically, the GCC operates with six member countries rather than 27, making the transition from national initiatives to regional integration tractable in ways that Europe's structure renders increasingly difficult. The goal is sequential coordination: build national compute capacity rapidly, then cohere it regionally — avoiding both the paralysis of waiting for perfect regional consensus and the waste of permanent fragmentation.

More fundamentally, the GCC should collectively recognize that AI infrastructure represents a geopolitical choice, not merely a capital deployment decision. The question is not whether to build compute capacity, but what kind of strategic position that capacity enables and which broader architecture it reinforces. Simply building data centers risks creating stranded assets — expensive infrastructure without the technical ecosystem, talent pipeline, or market access to make it productive.

The risk is real. History offers cautionary examples of massive infrastructure projects that failed to generate anticipated returns because they were disconnected from broader strategic context or lacked the complementary capabilities needed to translate hardware into productive output. China’s “ghost cities” provide a vivid illustration: meticulously constructed urban districts that remained hollow for years because the physical buildout raced ahead of the economic logic required to sustain them. To avoid this scenario, the GCC must develop a roadmap that articulates not just what infrastructure to build but why it matters and how it connects to measurable strategic outcomes: enhanced national security capabilities, diversified economic activity beyond hydrocarbons, positioning in global technology supply chains, spillover effects across surrounding Arab states, and genuine agency in an AI-defined international order.

Why the Gulf, Why Now?

The 20th century was dominated by industrialization, regional power shifts, and technological revolutions that reshaped the geopolitical landscape. From the two World Wars to the Cold War, the United States witnessed immense growth not only in strength and political power but also in technological advancement. Industrialization brought economic growth on a scale the world had never seen before, which brought forth technological advancements in every field. These advancements ranged from the iPhone to nuclear weapons and everything in between, all of which contributed to the nature of geopolitical power structures. Together, these factors have set the stage for the newest technological innovation: compute.

Power structures will no longer be dictated solely by munitions and access to resources like oil but increasingly by compute: which states possess it and who controls access to it. Compute may prove just as important as traditional power assets — if not more so. In the 20th century, the Gulf gained power not because of its armies but because of its access to oil reserves. Capital from oil funded everything for states such as Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar, and the rest of the GCC. However, as the world moves toward decarbonization, the Gulf must look beyond its natural resources and expand its economy through diversification. As these changes unfold, the justification for international AI partnerships is reflected in the new strategic importance of compute and the interests of all parties intent on capturing its value.

A US-GCC AI Partnership fits the bill. From the American perspective, the Gulf offers abundant, reliable, and cheap energy to support its firms’ AI training and inference. From the Gulf’s perspective, access to American-designed chips for training and inference[24] is crucial to catapulting the region into a force multiplier for the diffusion of a secure, scalable, American-aligned AI ecosystem.

This convergence of America’s need for energy and compute capacity with the Gulf’s need for chips and technical expertise creates natural conditions for partnership. However, realizing this potential requires moving beyond abstract complementarity to concrete frameworks that address the specific bottlenecks each side faces. The case for partnership becomes clearer when examining these constraints directly.

First, it bears noting that the Gulf is not a monolith. There is a real AI readiness gap between states. The UAE started early, building regulatory frameworks, data center density, and deep AI partnerships. Saudi Arabia has the scale and capital and is now building the institutional muscle required to execute compute buildup at speed. Qatar, Oman, Kuwait, and Bahrain have varying levels of ambition and technical capability, with some prioritizing AI while others are exploring alternative technological bets such as quantum computing. These disparities matter — and any US strategy must engage the Gulf as it actually is, rather than as it wishes the region to be.

Some critics argue that existing political divisions between Gulf capitals make a unified technological foundation impossible. However, the strategic picture is changing. In the aftermath of the 2025 Doha attacks, Gulf states have begun seriously considering collective security arrangements, including joint air-defense systems and broader regional security architecture.[25] If the region is moving toward shared security, then a framework for coordinated AI compute infrastructure is not as far-fetched as skeptics suggest. Divergent starting points do not undermine the overall direction of travel; they simply determine the pace. And the Gulf’s intense competition over trade, technology, and global positioning has — paradoxically — produced a kind of competitive convergence in which each state’s ambition accelerates the others.

The GCC Stack Is Energy Abundant

The feasibility and eventual success of the GCC stack is rooted in a core truth about the AI era: while AI is increasingly energy-constrained — and this represents a significant hurdle for other global players — the energy-abundant Gulf is exceptionally well positioned for a major AI compute buildup.[26]

While other nations are grappling with energy bottlenecks due to surging AI compute demand, the Gulf offers an abundant, stable, and scalable energy base. This gives the region a structural advantage. The Gulf’s surplus of oil, natural gas, and rapidly growing renewable capacity, paired with sovereign investment in nuclear power, makes it one of the few regions capable of hosting energy-intensive AI compute infrastructure at scale.

First and foremost, the GCC’s production capacity for oil is unparalleled, offering abundant energy at low prices. Additionally, the Gulf states have pursued aggressive diversification efforts to expand their production of renewable energy. The International Energy Agency (IEA) projects a 40 GW increase in the Gulf’s renewable power generation capacity by 2028.[27] This is more power than the UAE generated in 2024. Given the Gulf’s longstanding energy expertise and resources, combined with its commitment to renewable energy, there is no place better equipped to meet AI’s unprecedented energy demands.

In addition to traditional and renewable energy sources, the Gulf states are strategically investing in nuclear power, a crucial long-term solution for energy-intensive AI workloads.

The UAE’s Barakah Nuclear Power Plant has four fully operational reactors that supply a significant portion of the country's electricity. With a total capacity of over 5.3 GW, the plant has transformed the UAE's energy mix. The Emirates Nuclear Energy Company recently signed a memorandum of understanding with GE Vernova Hitachi Nuclear Technology evaluating the deployment of BWRX-300 small nuclear technology internationally, signaling the UAE’s ambition to play an important role in innovation in the field.[28]

Bahrain is also moving forward with a nuclear strategy. The kingdom recently signed a memorandum of understanding on cooperation with the US in a key step toward establishing a nuclear energy program for peaceful purposes. Saudi Arabia has plans to build its first nuclear power plant and has allowed inspection of its Duwayhin Nuclear Energy Company by International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) personnel in June 2025, in preparation for capacity buildout.[29] Following Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s recent trip to Washington, Saudi Arabia and the United States signed a cooperation agreement that lays the groundwork for a long-term partnership in civilian nuclear energy, with strict nonproliferation safeguards to ensure exclusively peaceful use.

Energy abundance alone, however, does not automatically translate into AI leadership. The Gulf's structural advantages in energy supply must be deliberately channeled into a coherent regional strategy that addresses the full spectrum of requirements for AI competitiveness. This necessitates examining what a mature GCC AI ecosystem would look like in practice. It must also work out how individual national initiatives can cohere into a federated regional stack that leverages collective strengths while avoiding the fragmentation that has hindered other regions' AI ambitions.

The Vision: A Regional AI Cluster

A Federated GCC AI Stack Amid Geopolitical Competition

As established, the six-nation GCC bloc boasts vast hydrocarbons resources, huge power-generation capacity, and some of the world’s largest SWFs. Leading funds like the Public Investment Fund (PIF) in Saudi Arabia are heavily focused on investing their money and resources into technology. The AI infrastructure boom is capital-intensive, and AI-oriented Gulf money is already a major player in funding American AI labs and their compute buildup.

In the context of the GCC AI stack, the distinction between the infrastructure and application layers becomes increasingly important. The infrastructure layer — chips, data centers, and energy — must remain closely aligned with the United States and Europe. NVIDIA and AMD dominate the chips, and American hyperscalers still run the largest-scale clouds. For the GCC, this means ensuring access to GPUs, securing trusted cloud zones, and building out massive energy-backed data centers across Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar. Coordination, not competition, is the focus — synchronizing data center buildouts, integrating electricity grids, and adopting shared security and compliance protocols. If the GCC speaks with one voice at the infrastructure level, it guarantees access to compute and avoids duplication.

AI will not only be shaped by who builds the models, but also by who builds the compute infrastructure. The GCC is in the unique position of having the ability to develop a cross-border AI cluster that uses shared models and energy. With anchors in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, this cross-border cluster will boost each GCC state’s AI competitiveness while lowering overall cost for the region.

Infrastructure Foundation

The GCC Interconnection Authority (GCCIA) connects the power grids of the bloc’s states in order to ensure that, in the case of blackouts or grid overloads, each state is able to share the burden with its neighbors. The GCCIA has a maximum capacity of 1.2 GW.[30] The Gulf is not the first region to use an interconnected grid system. The United States, for example, has connections with Canada, and the Synchronous Grid of Continental Europe, a large, interconnected grid, covers a wide area of Europe.

We propose an expansion of this connection from being used only during emergencies to being used for AI power availability, allowing for burden sharing across the region. This expansion could also include collaborative investment in data center infrastructure, as new centers will impose a large strain on each state's current grid. Instead of each state having its own electricity grid and its own set of data centers, working collaboratively will allow for lower costs and greater rewards.

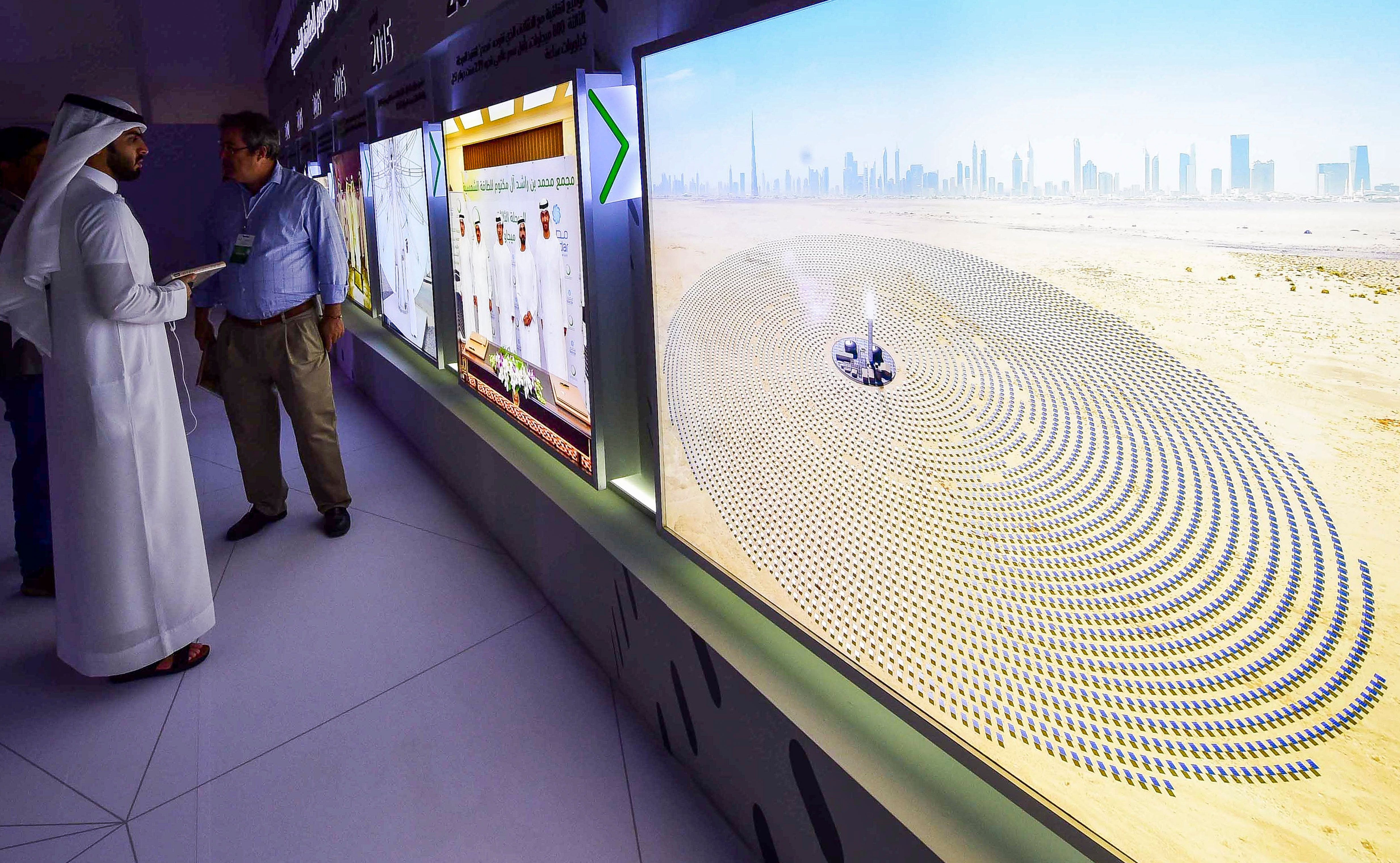

As the International Institute for Strategic Studies’ Laith Alajlouni and Jasim Murad noted in May 2025: “In 2023, data centres worldwide consumed approximately 500 terawatt-hours of electricity, or roughly the equivalent of Germany’s annual consumption, and this is expected to triple by 2030.”[31] Currently, Qatar, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia are some of the world's largest energy providers, making them key locations for large-scale data centers. HUMAIN in Saudi Arabia has plans to establish 1.9 GW of data center capacity by 2030, increasing it to 6.6 GW four years later,[32] and the project has attracted strategic partnerships with American firms like NVIDIA and Qualcomm.[33]

The Gulf’s ambitions regarding AI infrastructure specifically, beyond energy provision, have already begun to materialize. Stargate UAE is a part of plans for a larger, 10-square-mile data center site, which will eventually host 5 GW worth of data centers.[34] The UAE already has 34 data centers, while Saudi Arabia currently has 36 and Qatar has 11.

This infrastructure foundation creates the physical backbone for AI operations at scale. But infrastructure hardware is merely the enabling layer. The strategic value of a federated approach emerges when examining how this shared foundation translates into operational advantages and competitive positioning.

The main benefit of a federated AI ecosystem is that it reduces redundancy. If each state needs to develop a certain number of data centers in order to run large-scale AI models, would it not be easier for the states to develop one-third of the amount and share the burden with their neighbors? This model could also be replicated in other areas of the world that are rich in energy but not as prepared to make a large investment in infrastructure.

The Gulf has the ability to become an important node in global AI compute. The GCC possesses all of the components needed to become a back-end infrastructure powerhouse in AI. It is able to offer the world large-scale compute through data centers, an abundance of land, and reliable energy sources. Today, the Gulf is a consumer of foreign AI, with the majority of its models, tools, and infrastructure being imported from other states, mostly the US. However, with targeted investments and strategic coordination, the GCC can transition from end-user to a major global stakeholder in the AI ecosystem.

A complete AI stack requires not only abundant compute capacity and cutting-edge hardware, but also a robust ecosystem encompassing data management, advanced software development tools, skilled talent, and a strong enterprise layer. Large-scale compute depends heavily on reliable, always-on energy infrastructure to power intensive operations efficiently. Sustaining innovation further demands access to expert researchers and engineers, along with a secure supply chain for critical technological components, chief among them AI chips. Without these interconnected elements working seamlessly together, efforts to scale AI compute risk falling short.

Compared with Europe and South Asia, the Gulf faces fewer constraints. The GCC offers cheap and scalable energy, while Europe has high energy costs. Europe, despite being research-focused, lacks the capacity to develop infrastructure to scale. It also has strict privacy laws. Furthermore, the region has been highly affected by the Russo-Ukrainian war when it comes to access to energy, making it harder to rapidly scale AI data centers. Despite programs like the European High Performance Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC JU), which has participating states contribute resources to make the region a leader in supercomputing,[35] Europe still lacks an active continent-wide compute initiative. The same goes for South Asia, which has the ability to scale AI but lacks some of the fundamentals needed to do so as quickly as the Gulf. While Europe and Southeast Asia are investing heavily in AI, neither one has the capability to maintain a full AI stack and compete in global AI infrastructure.

As noted, energy capacity and even a federated stack will not be enough for the GCC to fully develop its own AI stack. The relative scarcity of advanced chips and fierce global competition over the attraction and retention of AI talent require that Gulf states expand upon existing international partnerships, including commercial, technical, and geopolitical ones. Building upon existing ties with American firms, in particular, would allow the GCC to secure a reliable supply of chips and facilitate talent exchange while firming up the foundations of its regional compute infrastructure in alignment with the United States.

The Case for a US-GCC AI Partnership

This vision for the GCC is one of an integrated electricity and data center grid, positioned as an AI back-end cluster, led by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Qatar, with significant involvement from Bahrain, Oman, and Kuwait.

This vision intersects directly with the needs of the United States as it attempts to maintain and expand its own technological lead in the years ahead. In particular, the suitability of GCC states as a regional AI stack — complete with AI data centers, land on which to build them, and the energy to power them — provides strong justification for a US-GCC AI partnership.

Before turning to specific recommendations for this partnership, the arguments, in brief, are provided below.

Energy and Chip Supply

The most immediate and obvious bottleneck faced by US-based AI firms today is securing access to a reliable supply of energy for model training and inference hosted by data centers. Whereas factors in model development like training data can be circumvented through methods like human subject-matter data annotation[36] (albeit, at slower paces than what the industry is accustomed to), energy supply is something of an all-or-nothing affair. Either the infrastructure, built upon suitable land, to supply reliable energy exists or it does not.

The number of states with the necessary energy capacity and willingness to intertwine various AI ecosystems for mutual benefit is quite limited. The GCC has a major competitive advantage here, as it works to build out its domestic AI ecosystems and is equipped with ample energy supply from hydrocarbons while actively transitioning to renewable sources as states diversify their revenues.

Likewise, GCC states face their own bottlenecks, chief among them a sufficient supply of chips suitable for AI training and inference — a core component of the May 2025 US-Gulf leadership meetings. The US, with a commanding lead thus far in the design of such chips, has something of interest to GCC states. The US likewise is home to a disproportionate share of the world’s AI talent, a resource of no small importance beyond the availability of both energy and chips.

Geopolitical Opportunity Costs

Global demand for compute is growing exponentially and will continue to do so for the foreseeable future. Meeting this demand requires a comprehensive infrastructure strategy that maximizes buildout across multiple geographies rather than treating partnerships as mutually exclusive.

Some have suggested that the US concentrate AI infrastructure development exclusively among traditional allies such as Canada, Norway, Finland, and Australia.[37] While these partnerships remain essential and should be strengthened, limiting infrastructure development to this network alone would be insufficient to meet projected compute requirements. Moreover, America's relationships with these allies are sufficiently robust that they do not depend on monopolizing all strategic technology initiatives within this sphere.

A more effective approach would involve three parallel tracks:

First, accelerate domestic data center construction and compute capacity within the United States and among its closest allies. These partnerships form the foundation of American AI infrastructure and should be maximized.

Second, simultaneously develop strategic compute partnerships with GCC states. These countries offer distinct advantages: substantial energy resources, significant capital for infrastructure investment, strategic geographic positioning, and strong alignment of interests in AI development. The emerging EU-GCC AI partnership demonstrates the viability and international interest in this model.

Third, establish interconnected infrastructure networks that create a globally distributed yet strategically aligned compute ecosystem. This could include linking GCC infrastructure with Europe, creating redundant, geographically diverse compute capacity.

The strategic calculus is clear: America's alliances with Western allies can be maintained and strengthened independent of whether all AI infrastructure development occurs within that network. By contrast, American influence in the Gulf region risks significant erosion if the United States does not engage while strategic competitors do.

This is not a choice between Western allies and GCC engagement but rather a question of meeting exponential compute demand through strategic diversification versus imposing artificial constraints that limit American technological leadership. The key, however, is resolving the logistical constraints that make chips a de facto cap on global scaling. In theory, without additional upstream fabrication capacity, allocation inevitably risks becoming zero-sum — every chip deployed in the Gulf could mean one less available for Europe or other allied markets. But in reality, Europe should have aspired to serve as the regional backbone for next-generation compute, capable of supplying the energy, capital, and industrial scale required; instead, the Gulf has stepped into that role. As the region accelerates its AI-infrastructure buildout toward gigawatt-scale compute — even while it will remain in the single-digit-million-chip range for several years — it is now occupying the position Europe has not managed to fill. This is precisely why expanding the footprint of Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), the world’s largest dedicated semiconductor foundry — including the possibility of a future presence in the Gulf — would strengthen, not weaken, allied AI scaling. It would shift the region from a passive recipient of scarce chips into a strategic source of fabrication capacity embedded within the US-aligned ecosystem. The recommendation section below outlines this framework with appropriate security safeguards and governance mechanisms.

The strategic logic for a US-GCC AI partnership is clear: exponential compute demand and the imperative to prevent the emerging Chinese AI ecosystem from filling the vacuum. Translating this strategic alignment into operational reality, however, requires specific policy actions on both sides. The recommendations below outline concrete steps the United States and GCC states should take to build this partnership effectively.

Recommendations

What the US Should Do

In order for the Gulf to build an integrated electricity and data center grid, it needs coordination from the US. The GCC also needs American technologies to build its AI infrastructure. This benefits both parties. The GCC gains access to the US’s unparalleled AI compute resources, while the US gains access to the GCC’s AI infrastructure for its own technological advancement.

This partnership requires regulatory clarity due to the complexities of the underlying technologies involved and the pace of AI development. Thus, the US should designate the GCC countries as trusted AI allies. Regulatory clarity means the GCC should receive a framework that provides the predictability, speed, and coordination required for a multi-gigawatt AI buildout. This clarity is, at its most basic level, an indication that building advanced AI compute in the Gulf should not be encumbered by stringent approval processes. Imposing overly strict US export controls on the GCC would cause unnecessary delays in constructing the Gulf’s data center capacity. Completing this project as soon as possible is in the interests of both the US and the GCC.

In this respect, the US may build off its AI Acceleration Partnership with the UAE established in May 2025. The US Bureau of Industry and Security (BIS) approved the first wave of chip exports to the Emirates under this arrangement in October 2025, as the UAE’s commitment to a reciprocal US investment was confirmed (notably, these approvals are merely the first step of implementation).[38] A US-GCC partnership would necessarily broaden the scale and scope of such export and, in turn, see the intertwining of American technology with Gulf technology buildouts.

Beyond streamlining export licensing (handled by the Commerce Department’s BIS), the US should reform the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS) review process to clarify expedited pathways for trusted Gulf sovereign capital into the American AI stack. CFIUS is a national-security, risk-based screen (separate from export controls) that assesses transactions case by case, including those involving foreign government-controlled investors.

While a small set of “excepted foreign states” (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom) receive certain carve-outs as members of the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing pact, all other partners fall under a different review posture. Outside the Five Eyes, CFIUS applies heightened scrutiny where appropriate and offers safe-harbor options such as sub-10% passive stakes, which limit an investor’s ability to control or influence management of a company, and other structuring tools. This distinction matters because the Gulf states are now among the United States’ most important sources of capital for AI infrastructure and chip manufacturing, and the US-GCC tech partnership requires a far clearer, more predictable, and more streamlined review process. Providing improved guidance and time-bound timelines would prevent prolonged uncertainty that leaves Gulf capital in a gray zone and would reduce friction for partnerships aligned with US interests.

At the same time, it is important to recognize that investment screening mechanisms such as CFIUS are inherently bilateral. The US assesses trust, safeguards, and end-use controls separately for each country. Within this framework, each Gulf country must independently meet technology criteria while still developing complementary capabilities by aligning individually with US national security standards. Given this reality, the next step is to adapt the system to today’s strategic landscape.

The US should establish an expedited CFIUS track for investments from designated trusted AI allies, with pre-cleared investment categories for semiconductor facilities, data center infrastructure, and AI research partnerships. Such a framework must be tied to clear conditions around end-users, on-site personnel, physical geolocation of assets, and the identification of core versus secondary technological partners. This reform would clarify investment policy uncertainty that currently deters Gulf capital from flowing into American AI ventures at the scale both sides require. Clear, predictable approval pathways — combined with appropriate safeguards for genuinely sensitive technologies — would unlock billions in Gulf investment while maintaining necessary security protections.

Additionally, the US should support talent exchange and establish AI research and development (R&D) partnerships with the GCC. AI R&D is a priority for both partners, and joint efforts allow each state to target outstanding improvements in frontier models for mutually desirable applications. The UAE has made health, for example, a significant part of its digital transformation agenda, investing heavily in telemedicine, AI-assisted diagnostics, remote monitoring tools, and mobile health platforms. The UAE’s digital health market is projected to grow at an annual rate of 23.5% and reach $2.6 billion by 2030.[39] Similarly, Saudi Arabia has expanded its pharmaceutical manufacturing and launched national genomics programs under Vision 2030.

Likewise, in the United States, R&D funded by the National Science Foundation has shown interest in health applications, in particular by improving the trustworthiness, reliability, and analytic depth of generative AI models in clinical environments[40] — a goal likely shared by the GCC. At the same time, major private actors like OpenAI have released flagship models, including GPT-5, with noted designs on health applications,[41] while OpenAI investor Microsoft entered into a licensing agreement with Harvard University’s graduate medical school for access to the latter’s consumer health information.[42]

Beyond these domestic initiatives, there are some promising collaborations between the US and the Gulf states, including Abu Dhabi-based G42’s establishment of a joint task force with the Ohio-based Cleveland Clinic to scope out potential AI applications of mutual, health-related interest.[43]

Basic R&D, however, is still needed. This work can and should be carried out amid a US-GCC partnership. The easing of regulatory measures aimed at restricting the flow of advanced chips and related technologies would facilitate the exchange. AI talent disproportionately concentrated in the US can likewise leverage the capital that the GCC is deploying to health-related R&D. Opportunities beyond clinical domains immediately present themselves: with increased scrutiny of Chinese investment in sensitive sectors, American biotech startups seek trusted funding sources. Gulf SWFs could fill that gap — fueling American innovation while strengthening geopolitical alignment.[44] Their respective strengths should be leveraged.

Finally, the US should take more diligent steps toward the onshoring of critical components in the chip supply chain. Such efforts began with some force in 2022 with the passage of the CHIPS and Science Act, in part aiming to incentivize the local manufacturing and production of semiconductors. However, far more work is needed to firm up the US’s leadership in the domain it currently leads — advanced chips for AI model training and inference. In this way, US policymakers can build off existing international collaboration between Saudi Arabia’s PIF, Qatar Investment Authority (QIA), Kuwait Investment Authority (KIA), the UAE’s Mubadala Investment Company, and American technology firms, including Apple, Microsoft, Google, OpenAI, Anthropic, NVIDIA, AMD, Qualcomm, and Intel, to invest in onshore semiconductor manufacturing and packaging through complementary efforts.[45]

What the GCC Should Do

GCC efforts to independently build out its AI stack should revolve primarily around energy infrastructure expansion and integration across the region, workforce upskilling and talent cultivation, investment coordination, digital regulation harmonization, and the establishment of AI laboratories and pilot zones for experimentation.

First, the GCC should prioritize the development and expansion of energy infrastructure across the region with the goal of achieving grid and data integration to meet AI demand. The GCCIA should lead this effort. According to the head of the GCCIA, the agency is currently adding interconnections between Kuwait and Iraq in addition to the ongoing connection between Saudi Arabia and Egypt.[46] It is also planning to expand its grid to connect Oman.[47] Additionally, the agency is exploring establishing a pan-Arab electricity market in the near future.[48] These grid expansion efforts will be crucial for establishing the GCC as a leader and indispensable ally in AI and should be supported as such.

The GCCIA effectively manages a unified power grid that allows electricity to flow across member states and should build on the existing cooperation infrastructure. The interconnected grid acts as a safety net that ensures a reliable energy supply, protects against blackouts, and delivers an affordable, sustainable power option.[49] If the GCC can successfully coordinate energy infrastructure across borders, it would point to the possibility of coordinating compute infrastructure as well. Simultaneously, joint investments in regional subsea cable networks have established shared digital pathways. These examples emphasize that economic incentives can foster cross-border coordination even in the absence of a unified political framework. The development of a regional AI compute network is likely to follow this proven pattern.

In parallel with energy infrastructure expansion, the Gulf should, secondly, build an integrated computing network that pools computing resources across public and private data centers in the region. This will optimize the allocation of compute resources. Since 2024, China has been building a national integrated computing network to accelerate its AI development and digital transformation.[50] The GCC can adopt a similar framework to manage its compute resources more effectively. For example, the UAE and Saudi Arabia both have more than 30 data centers, but Bahrain and Kuwait only have five and four, respectively.[51] Creating a centralized computing network will promote AI readiness across the region, leaving no country behind. Presenting a unified front will only strengthen the GCC’s posture on the global stage.

For example, the GCC could initiate a Council-wide effort to develop and deploy regionally trained LLMs that would be able to operate both in Arabic and in English. The initial model training would take place on GPU clusters across data centers in the UAE and Saudi Arabia. Each state would contribute compute as part of a collaborative AI training structure. Next, in compliance with each state’s data sovereignty laws (which should be made more interoperable), shared data sets would be locally stored in each state but accessible across borders. The result would be an AI service that would be accessible to government agencies and other groups as selected by each state. This would create a federated AI ecosystem that balances national sovereignty with burden sharing across the region.

Third, revamping education to cultivate an AI-ready workforce and develop talent means incorporating AI into standard curricula in primary, secondary, and higher education. The Gulf may look to China’s premier AI lab, DeepSeek, as an example: more than half of the AI researchers employed by the start-up were trained only in Chinese universities.[52]

Upskilling in AI should be a goal not only among the GCC countries but for their neighbors, as well, such as Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Pakistan, India, and Morocco. Investing in AI education in the GCC will have a natural spillover effect in the region. Nevertheless, where possible, coordination or mutual influence in the construction of relevant curricula should be sought out by individual Gulf states.

Fourth, the GCC countries should align their digital jurisdiction laws to minimize regulatory risks and uncertainty for companies seeking to use their AI stack. Right now, the Gulf states have different cross-border data transfer laws. This patchwork of regulation will turn AI companies away from adopting the GCC AI stack and impede progress. The GCC states must agree on a single digital framework to maximize their appeal to foreign investors.

Next, to coordinate investment across the region, the GCC should create a GCC AI Investment Fund. The AI Infrastructure Partnership (AIP), which was established by BlackRock, MGX, Global Infrastructure Partners (GIP), and Microsoft to raise capital in response to the pressing need for AI-ready data centers and energy solutions, is an example of how this initiative could operate. This GCC fund would pool capital from across the region and invest in large-scale projects that benefit the entire region. Kuwait’s KIA recently joined the AIP, demonstrating a spillover effect, and the US should encourage other Gulf SWFs to join, such as the QIA, Oman Investment Authority, and Saudi Arabia’s PIF.

In parallel with joining the AIP, the GCC should encourage its major banks to establish AI industry-focused lending programs. These programs will support both basic research and application-specific R&D, providing entrepreneurs with the financing mechanisms necessary to produce innovations. More specifically, the GCC should launch a dedicated public funding program for AI-related intellectual property and applications. This funding will bolster innovation in areas that require proprietary protections. Such lending will incentivize use-inspired R&D. This represents the software model of the AI stack, at which step user-friendly products are created and diffused across the region.

Additionally, every GCC country should build its own AI regulatory sandbox and testing regime to support the final step before an AI product is released. Together, the GCC AI stack can comprise and offer support for the whole package — from training to testing.

Since 2019, the UAE has aspired to become the world’s AI regulatory testing ground and write the rules for global AI governance.[53] OpenAI’s Sam Altman saw the country’s potential in this regard.[54] The UAE’s early creation of the AI regulatory sandbox Regulations Lab set itself up to become a leader in AI testing. Likewise, a priority within all GCC countries' AI strategies is to accelerate AI research and talent development.

Taken together, the GCC countries should establish AI laboratories and pilot zones in every Gulf capital and business center. National capitals and business centers are the ideal locations to gather domestic and international talent. Once established, these AI labs and specialized zones would provide a basis for talent exchange and joint R&D efforts with the US.

The GCC should also, as a matter of shared purpose, support open-source AI. Open-source AI refers to AI models that are publicly available for download and modifications. Promoting open-source AI can spur innovation and encourage collaboration across the GCC AI ecosystem, allowing less-resourced but aspiring developers to use such models as tools for further experimentation and refinement for specific applications. The US government has voiced its support for open-source AI,[55] making it a worthy point of alignment for the GCC.

Conclusion

The AI era demands a fundamental rethinking of strategic infrastructure and international partnerships. Just as oil shaped the geopolitical landscape of the 20th century, compute infrastructure will define power relationships in the 21st. The GCC stands at an inflection point, positioned to leverage its historical advantages in energy while building new capabilities in the technologies that will shape the future.

The GCC AI stack represents more than an infrastructure project. It embodies a strategic choice about which technological ecosystem the Gulf will integrate with and which broader architecture it will reinforce. The region’s structural advantages — abundant and scalable energy, massive, concentrated capital, geographic positioning, and political coordination — create genuine potential for the Gulf to emerge as a third major node in global AI infrastructure, commercially and technically aligned with American firms while serving emerging markets across the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia.

This vision is achievable, but only if both the United States and GCC countries act with clarity and urgency. The window for establishing this partnership is finite. China is actively building and diffusing its own AI stack across the developing world, offering an alternative ecosystem that, while technologically behind American capabilities today, addresses real market needs with competitive pricing and fewer regulatory hurdles. The question is not whether emerging markets will build AI capacity but whose technology standards and commercial partnerships will undergird that capacity.

For the United States, the Gulf offers what domestic expansion alone cannot provide: the energy and capital to scale AI infrastructure at the pace demanded by exponential compute growth, geographic positioning to meet demand in large underserved markets, and political alignment that makes deep technology integration feasible. American chip producers, cloud providers, and AI labs need places to deploy their technology at scale. The Gulf provides that opportunity while keeping compute capacity within the US-aligned ecosystem rather than ceding ground to competitors.

For the GCC, partnership with the United States provides guaranteed access to the world’s most advanced AI chips, technical talent concentrated in American universities and companies, and integration into the technology architecture that will define the coming decades. More fundamentally, it offers a pathway to economic diversification that leverages existing strengths — energy and capital — while building new capabilities in AI operations, talent development, and technology services. The alternative is not preserving the status quo but watching neighboring regions adopt Chinese technology standards while the Gulf’s energy advantages become stranded assets in an AI-defined economy or, worse, become aligned with an emerging Chinese stack.

The recommendations outlined in this report provide a concrete roadmap. The United States must designate GCC countries as trusted AI allies, reform CFIUS procedures to expedite Gulf investment in American AI infrastructure, support talent exchange and joint R&D partnerships, and accelerate onshoring of critical chip manufacturing components. The GCC must prioritize energy grid expansion and integration, build an integrated computing network that pools regional resources, revamp education systems to cultivate AI-ready workforces, harmonize digital regulations, coordinate investment through a GCC AI Investment Fund, and establish AI laboratories and pilot zones across the region.

These actions are mutually reinforcing. American chip exports enable Gulf infrastructure buildout, which in turn provides American firms with massive new compute capacity for training and inference. Gulf investment in US semiconductor manufacturing strengthens supply chains while deepening commercial ties. Talent exchange programs build the human capital both sides need while fostering the long-term relationships that make technology partnerships durable.

The stakes extend beyond the immediate parties. Success in building a GCC AI stack aligned with US technology creates spillover effects across neighboring states — Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Pakistan — bringing them into an AI ecosystem built on Western standards rather than Chinese alternatives. It demonstrates to emerging markets globally that partnership with the United States offers a viable path to AI capability. It establishes precedents for technology cooperation that can be replicated with other strategically positioned regions.

The transition from crude to compute is underway. The Gulf’s choice is whether to lead this transformation or watch from the sidelines as others shape the AI architecture of the coming decades. For the United States, the choice is whether to embrace strategic partners who can help meet exponential compute demand or impose artificial constraints that cede ground to competitors. The path forward requires both sides to move beyond incremental steps toward a comprehensive partnership that matches the scale of the opportunity and the urgency of the moment.

Endnotes

[1] Aadya Gupta and Adarsh Ranjan, “A Primer on Compute,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, April 30, 2024.

[2] TAS News Service, “GCC countries hold top spot in crude oil production, reserves, and exports,” The Arabian Stories, February 15, 2025.

[3] GCC Statistical Centre, “Total GCC Electricity Production, 2023,” GCC-Stat Data Portal, accessed 3 December 2025.

[4] “The Impact of Cloud Services in the United States,” Public First, 2022.

[5] The White House, “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” July 2025.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Robi Rahman, “The NVIDIA A100 Has Been the Most Popular Hardware for Training Notable Machine Learning Models,” Epoch AI, October 23, 2024.

[8] Dylan Patel, Daniel Nishball, Myron Xie, Patrick Zhou, Ivan Chiam, AJ Kourabi, Christopher Seifel, and Doug OLaughlin, “Huawei AI CloudMatrix 384 – China’s Answer to Nvidia GB200 NVL72,” SemiAnalysis, April 16, 2025.

[9] Grace, George, “World’s Largest Data Center: China Telecom Inner Mongolia Park,” June 18, 2023.

[10] Dylan Patel, Daniel Nishball, Myron Xie, Patrick Zhou, Ivan Chiam, AJ Kourabi, Christopher Seifel, and Doug OLaughlin, “Huawei AI CloudMatrix 384 – China’s Answer to Nvidia GB200 NVL72,” SemiAnalysis, April 16, 2025.

[11] Patricia Cohen, Keith Bradsher, and Jim Tankersley, “How China Pulled So Far Ahead on Industrial Policy,” The New York Times, May 27, 2024.

[12] NBP, “500 by 2050? Inside China’s massive nuclear expansion and its global power shift,” Nuclear Business Platform, May 14, 2025.

[13] Colleen Howe, “China’s solar power capacity growth to slow in H2 after pricing reforms,” Reuters, August 13, 2025.

[14] Ryan Kennedy, “US Total Solar Capacity to Double over Three-Year Span,” PV Magazine USA, April 11, 2025.

[15] Chunqan Zhu and Carol Zhou, “How Chinese Enterprises Are Acting on Climate by Meeting China’s Dual-Carbon Goals,” World Economic Forum, July 27, 2023.

[16] Eric Blumrosen, “The Evolving Mix of the Energy Sources for the US’s Electric Generating Capacity,” The National Law Review, September 24, 2024.

[17] Jan Yong, “Malaysia caught in crosshairs of US – China AI race,” W. Media, May 20, 2025.

[18] David Kirton and Mo Yelin, “China's Huawei opens cloud data centre in Saudi Arabia in regional push,” Reuters, September 4, 2023.

[19] JD Vance, “Remarks by the Vice President at the Artificial Intelligence Action Summit in Paris, France,” The American Presidency Project, February 11, 2025.

[20] Anton Leicht, “Data Center Delusions,” Threading the Needle, July 16, 2025.

[21] “European Chips Act,” European Commission, September 29, 2025; “European Research Development and Deployment of Ai,” European Commission, October 8, 2025.

[22] Cristinia Caffarra, et. al.,“The White Paper,” EuroStack, May 19, 2025.

[23] Cokelaere, Hanne, and Gabriel Gavin, “Despite Draghi, Europe’s Energy Price Crisis Has Gone Nowhere,” Politico, September 9, 2025.

[24] AI inference is the process by which a trained model applies what it has already learned to generate outputs — predictions, classifications, or real-time decisions — when deployed in the real world. Unlike training, which is compute intensive and done once, inference runs continuously and at scale, powering everything from chatbots to autonomous vehicles.

[25] Agnes Helou, “Gulf States Pledge Increased Missile Defense Cooperation After Israeli Strike in Qatar,” Breaking Defense, September 18, 2025.

[26] Mohammed Soliman, “Energy, Not Chips, Will Determine AI Supremacy - and Here, It’s Advantage Gulf,” Indian Express, May 21, 2025.

[27] IEA, “Renewable electricity capacity growth by country or region, main case, 2005-2028 – charts – data & statistics,” International Energy Agency, January 11, 2025.

[28] WNA, “MoU paves way for further collaboration on BWRX-300 deployment,” World Nuclear News, 27 May, 2025.

[29] Sinead Harvey, “IAEA Launches Management System Advisory Service to Support the Introduction of Nuclear Power, Conducts First Mission to Saudi Arabia,” International Atomic Energy Agency, June 24, 2025.

[30] Robin Mills, “GCC Grid Infrastructure and Connectivity – An Electrifying Vision,” AGSI, August 29, 2023.

[31] Laith Alajlouni and Jasim Murad, “The uncertain dividends of AI in the Middle East,” IISS, May 27, 2025.

[32] Sebastian Moss, “Saudi Arabia’s AI co. Humain looking for US data center equity partner, targets 6.6GW by 2034 with subsidized electricity,” Data Center Dynamics, May 28, 2025.

[33] Press Release, “HUMAIN and NVIDIA Announce Strategic Partnership to Build AI Factories of the Future in Saudi Arabia” NVIDIA, May 13, 2025; Press Release, “Qualcomm and HUMAIN to Develop State-of-the-Art AI Data Centers to Deliver Cloud-to-Edge Hybrid AI Services,” Qualcomm, May 23, 2025.

[34] Stephen Nellis, “'Stargate UAE' AI datacenter to begin operation in 2026,” Reuters, May 22, 2025.

[35] EuroHPC JU, “Discover EuroHPC JU,” European High Performance Computing Joint Undertaking, accessed November 2025.

[36] Human subject-matter data annotation is the process by which human experts with domain-specific knowledge manually label, categorize, or tag raw data (text, images, audio, etc.) to make it understandable for training and refining artificial intelligence and machine learning models. See: Cem Dilmegani and Özge Aykaç, “Human Annotated Data,” AIMultiple, June 12, 2025.

[37] Alasdair Philips-Robins and Sam Winter-Levy, “Don’t Offshore American AI to the Middle East,” Foreign Policy, May 8, 2025.

[38] Mackenzie Hawkins, “US Approves Some Nvidia UAE Sales In Trump AI Diplomacy Step,” Bloomberg, October 9, 2025.

[39] “Middle East: The emerging global hub for digital health innovation,” Gulf Business, July 8, 2025.

[40] Manas Gaur and Amit Sheth, “Building Trustworthy Neurosymbolic AI Systems: Consistency, Reliability, Explainability, and Safety,” AI Magazine, February 14, 2024.

[41] OpenAI, “Introducing GPT-5,” August 7, 2025.

[42] Rishabh Jaiswal et. al., “Harvard Medical School Licenses Consumer Health Content to Microsoft,” Reuters, October 9, 2025.

[43] News Release, “Cleveland Clinic and G42 to Advance Healthcare Through Artificial Intelligence,” Cleveland Clinic, March 25, 2025.

[44] Mohammed Soliman, “The US should launch a Gulf biotechnology partnership,” Arabian Gulf Business Insight, May 14, 2025.

[45] Cody Combs & Kyle Fitzgerald, “UAE-backed GlobalFoundries plans $16bn investment to expand US semiconductor manufacturing,” The National, June 4, 2025.

[46] GGCIA, “Projects Under Construction,” GCCIA, accessed November 2025.

[47] GCCIA, “Our Plans,” GCCIA, accessed November 2025.

[48] “Towards an adaptable and resilient GCC grid,” The Energy Year, April 30, 2025.

[49] GCCIA, “GCC Interconnection Authority,” accessed November 2025.

[50] Liehong Liu, “Accelerate the construction of a national integrated computing network and promote the construction of a Chinese-style modern digital base,” QS Theory, March 16, 2024.

[51] Laith Alajlouni and Jasim Murad, “Data-infrastructure gap: data centres and AI preparedness in the Middle East,” IISS, May 27, 2025.

[52] Kyle Chan, Gregory Smith, Jimmy Goodrich, Gerard DiPippo, and Konstantin F. Pilz, “Full Stack: China’s Evolving Industrial Policy for AI,” RAND, June 26, 2025.

[53] Richard Sentinella, “How different jurisdictions approach AI regulatory sandboxes,” IAPP, May 14, 2025.

[54] Marissa Newman, “OpenAI’s Sam Altman Sees UAE as World’s AI Regulatory Testing Ground,” Bloomberg, February 13, 2024.

[55] Office of the President, “Winning the Race: America’s AI Action Plan,” The White House, July 2025.

Legal Disclaimer:

EIN Presswire provides this news content "as is" without warranty of any kind. We do not accept any responsibility or liability for the accuracy, content, images, videos, licenses, completeness, legality, or reliability of the information contained in this article. If you have any complaints or copyright issues related to this article, kindly contact the author above.